I recently attended a debate hosted by the New Statesman, the great political and cultural magazine founded by the Webbs in 1913. The motion was “The left won the twentieth century”, and I thought I’d give some brief thoughts on that theme. Defending the motion were Helen Lewis, Deputy Editor of the New Statesman; Simon Heffer, formerly of the Daily Telegraph and now writing for the Daily Mail (but amusing and intelligent despite this); and Mehdi Hasan, political editor of the UK Huffington Post. Opposing were Tim Montgomerie, founder and former editor of ConservativeHome; Ruth Porter of the Institute of Economic Affairs; and Owen Jones of ‘Chavs’ and increasingly ‘This Morning’ fame.

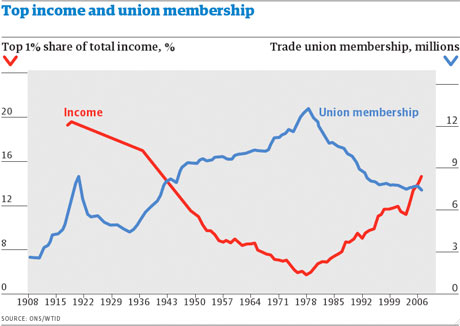

It was an excellent debate, and particularly interesting in that the result changed, with the audience voting against the motion before, and in favour at the end. I originally voted no, and ended up abstaining. Mehdi Hasan moved me slightly: in questions, I picked up on his claim that the left had “won the argument” on the NHS, the welfare state, etc. I pointed out that politics is not just conducted at the level of ideas, but of interests, and the comprehensive defeat of the labour movement since the 1970s was the most important issue of all, because on that movement was based all the achievements he described. He responded that that may be the case, but the fact remains that those institutions still exist. Although it is worth pointing out – contra Mr Heffer, who argued that all the achievements standing were of the left – that the creator of the welfare state was Otto von Bismarck, not exactly a man of the left. Indeed, there is a case to be made that the welfare state is one of the most powerful barriers to an increased radicalism, honeying over as it does the stark divisions that would otherwise come about.

Nonetheless tt was a good answer, and I was almost convinced. Above all, two of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century – decolonisation and the improvement in the condition of women – came from the left. But in the end I still didn’t vote for the motion. And here is why.

A young woman from Romania made a passionate case that the left failed her grandparents and parents because of the horrors of ‘socialism’ in her country. Mehdi Hasan, referring to a comment from Simon Heffer that the Soviet Union no less undermined the left than Hitler undermined the right, said this was not something that was relevant to the experience of the Western left. Owen Jones, when asked what lessons the left should learn from the USSR, said “the lesson to learn from totalitarian regimes is don’t be murderous totalitarian regimes!”

Both of these claims are problematic. Hasan and Jones seem to imply that the left – or rather, leftism – first: bears no responsibility for the Soviet/Eastern bloc experience and second: has nothing to learn from them (beyond the obvious political point that dictatorships aren’t very nice). But neither are obviously true.

Reference was light-heartedly made at the debate to the fact that Beatrice and Sidney Webb (who founded, as well as the New Statesman, the London School of Economics and the Fabian Society) were sympathisers with Soviet Communism. In 1935 they published the study “Soviet Communism: A New Civilization?” from which the question mark was later notoriously dropped. And yes, that is 1935, not 1925. Stalinism was in full swing and the purges were just around the corner. It just so happens that I was leafing through a copy last week; the section in which they defend Stalin against accusations of dictatorship are particularly hard to stomach.

But this is not a fluke result. Nor is this sort of Soviet apologetics unique to the Webbs and their middle class ilk. Who do you think said this in 1960?

I have not the slightest doubt that the economic measures and the Socialist measures which one will find in countries of Eastern Europe, will become increasingly powerful against the uncoordinated, planless society in which the West is living at present.

Fidel Castro perhaps? Erich Honecker? Nikita Khrushchev?

No. That would be James Callaghan speaking in the House of Commons. And this was not a particular eccentric view at the time: based on growth rates, the economist Paul Samuelson – author of the bestselling economics textbook in the world – predicted that the USSR would overtake the USA by the mid-eighties or late-nineties. Similarly, Noam Chomsky points out that much of the global conflict in the 60s and 70s was an attempt by the United States to suffocate “the Castro model of taking matters into their own hands” – that is, breaking away from the American liberal economic model and following the Soviet model of “modernisation in a single generation”. It’s also true that (until the 1970s, when the Eastern bloc began to stagnate) much of the opposition to Soviet hegemony came from socialist critique (eg. Czechoslovakia, Hungary), and not from Reaganite Cold Warriors.

So, from the 1930s to the 1960s, there was a strong sense in the Western left that a kind of centralised bureaucratic planning could overcome the messiness of market relations entirely, and that state ownership of industry – coupled with a kind of ‘Keynesian’ demand management – would be the model of the future. There is in this regard something awfully similar about this Fabian approach, and the practice of the Bolsheviks. The Webbs’ fondness for the Soviet model is the direct corollary of Beatrice’s criticism of worker cooperatives. For the Webbs, as for the Fabians and as for the Bolsheviks, socialism was a matter of intricate planning from on high.

This sort of approach is now highly discredited. Although it served well to develop poor societies (or redevelop rich ones broken by war), its capacity to meet the increasing complexities of the consumer society was unimpressive. The USSR became over-invested in heavy industry at the expense of consumer goods, and the vested interests of the central state (ie. the military) received a disproportionate share of the benefits of growth. The central planning model became sluggish and stunted, and the experience in the West with nationalisation was not much better.

So does this mean the left is a hopeless cause? Should we all just pack up, embrace David Cameron, and head home?

No!

We must return to first principles. We must distinguish between policies (which are the means) and the vision of society we would like to see (the end). Let us start with the vision, which must begin, in true dialectical fashion, with a critique:

- In entering a capitalist production process, workers submit to an unaccountable authority (the capitalist or his agent, the manager)

- This means the workers have no say in the process of production, or in what is done with the product once it is made, despite their having been instrumental in its creation

- This is undesirable because it distorts economic activity (production and employment become solely a means toward private profit and do not occur in its absence) and causes social harm (the worker becomes dehumanised and increasingly subject to economic forces beyond her control)

This is a diagnosis that I think the whole of the left – from anarchists to democratic socialists, communists to social democrats – could agree with. It is also something the right would vigorously disagree with. And notice what hasn’t been said. No reference has been made to markets, or money, or even to equality. No mention of planning. No mention of surplus value or crisis or effective demand. All these are matters for the left to fight over behind closed doors. The essential critique that all leftists can agree on is this: capitalism is not democratic. That is, in a capitalist society, capital is the determining factor of social organisation, and its decisions are not directly accountable to the people it effects.

Now in an age where industry flees to wherever wages are cheapest and the economy stagnates because capital refuses to invest, this critique seems to me to have lost none of its power. And if the problem in capitalism is the lack of democracy, it follows that the solution is to democratise the economy: to increase the degree of worker control over the process of production. (Incidentally, this is why New Labour was not leftist: it abandoned any aspiration to increase worker control in production, and replaced it with the conservative aim of a ‘property-owning democracy’. The crucial point – which the implosion of the housing bubble has handily shown – is that houses are not productive assets. A working class which owned their own homes – a middle class, in other words – would still have to turn up to work each morning in an autocratic workplace. You can’t eat your conservatory.)

One method of doing this would indeed be for the government to take ownership of all industry and have the workers as a whole determine economic matters through the ballot box. (Note that the fact workers could not do this in the Soviet Union immediately rules out its claim to be a socialist state; state ownership of industry is only socialist insofar as the state is accountable to the working class). This, in microcosmic form, is what happened in post-war Britain. I say microcosmic because even the Attlee Government only nationalised 20% of economic activity; British Coal or British Rail were therefore socialist enterprises, but Britain was not a socialist society.

But this is far from the only method. A workers’ cooperative would meet the same democratic standards. A society of corporations owned by wage-earner funds could arguably do the same. Indeed, some have argued that that is the precise direction in which modern society is moving. Large public providers – such as railways or schools – could be publicly owned and managed by councils of workers and consumers. And there is nothing in this vision which rules out the use of markets per se. Markets are a means of exchange; capitalism is a system of production. A society of worker cooperatives, funded through publicly owned banks and selling goods to market, would be a quite different species to a capitalist society in which investment and production is controlled by an unaccountable elite.

The key theme tying all these different options together (and why couldn’t society mix and match where appropriate?) is increased direct engagement by workers and consumers. The left lost the twentieth century because it limited itself to one model of economic democracy, dizzy with the apparent success of the Soviet Union. When that model – overcentralised, bureaucratic, unresponsive to people’s changing expectations – proved unable to adapt (and, in its own way, as alienating as any capitalist hierarchy) the right declared ‘THE END OF HISTORY!‘, and the left – its ideas hollowed out by decades of nationalisation – did not know how to respond.

Perhaps most important of all – and here the influence of classical Marxism has been unhelpful – the left fell into the trap of considering markets and capitalism the same thing (a little trick that the right very happily engage in, for talk of ‘the market economy’ very elegantly skips over the autocratic and unequal distribution of power and wealth). But markets are simply a method of exchange: they are neutral as to the content of the transaction (handbags, machines, people) and to the inputs of that transaction (who has market power?) From the perspective of exchange alone, the trade of goods between two farmers of equal wealth is qualitatively no different from the situation of a starving landless peasant who works sixteen hours a day for the lord of the manor in exchange for somewhere to live. From the perspective of exchange, both are acceptable because in both instances, both parties benefit relative to their prior position. The same argument is often made about child sweatshops: ‘Yes’, we are told, ‘it’s obviously horrible that kids have to work. But they do it because it’s better than being even poorer on the farm.’ The person making this case never seems to realise that just because it’s better for a child to work in a horrid factory than on a starving farm, it does not follow that working in a horrid factory is the optimal situation for a child. In a world as rich as our own, maybe we could find the resources to, I don’t know, send that kid to school?

So we must focus on the content of what is exchanged, and this becomes particularly important when talking about capitalism. For capitalism not a method of exchange (per se), but a method of production. When you and I trade Pokemon cards, we are not engaing in capitalism, we are engaging in…trade! Trade is exchanging goods and services for mutual benefit. This happens in all societies – even the USSR had trade. But this tells us nothing about where the goods came from in the first place. For that you need a system of production, not just exchange. If you employed your friends for a wage in the production of Pokemon cards and then sold them to me, then we’re into capitalist territory.

Capitalism is an economic system where the majority of the population sell their labour to the owners of capital in exchange for a wage. What that means is the worker surrenders control of the production process, and of the product, to the capitalist. Capitalism is characterised therefore by authoritarian relations of production. It is this authoritarian element in the workplace (and not the process of market exchange itself) which creates the most objectionable phenomena of capitalist society: the inequality, the warped investment decisions, the alienation, the use and abuse of the workforce. Indeed it is my contention – contrary to the communists – that the method of production is far more important than the method of exchange. Markets are an effective means of providing information and incentives. In this, Hayek was right and many socialists were wrong. Che Guevara’s attempt to create an economy motivated by ‘moral incentives‘ rather than material ones was a disaster. The point is that human nature is neither as bad nor as good as people like to imagine. It is shaped by its context and institutions. Democratising the workplace – worker control of production – would go a long way towards humanising the economy, and far more than the cold inhumanism of the USSR ever did.

Now, on the other side of the greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression, we can see what fatuous nonsense the ‘End of Hisory’ really was. The central insight of the left – that a society whose priorities are determined by capital is in conflict with the principle of democracy – still holds. The task for the twenty-first century is how to apply that understanding in the light of our failures last time. I will elaborate on this in future posts, but this is an outline of my position.