When the Roman emperors died, the greatest amongst them were granted an apotheosis – elevation to a divine level. The names of those given such an honour – Julius Caesar, Augustus, Claudius – are still known today. Politician-as-god might not quite be the view while they are alive (the Divine Clegg? the Divine Miliband?) but occasionally in death some alchemy takes place, and the zeroes become heroes for the ages.

Unless you live under a rock, or in an abandoned mining town, you’ll have probably noticed that the Iron Lady is dead. The nation is in mourning/jubiliation (delete where applicable). There has been endless media coverage for days (the Daily Mail seems to have temporarily forgotten immigrants exist), and such luminaries as Gorbachev, Obama and Harry Styles have all paid tribute. Perhaps the most melodramatic obituary came from Peter Oborne (a once interesting but increasingly preposterous man) in the aforementioned Mail, in which he claimed that “There were only two great British prime ministers in the twentieth century”, the other, of course, being Churchill. Apparently Attlee, Asquith and Lloyd-George never existed. Plans have been announced for a Thatcher Library, and she is to receive what essentially amounts to a state funeral. News Thump have satirised this instant-mythologisation (just add dead leader!) very nicely, with “Margaret Thatcher was first man on moon, claim Tories”.

Regardless of the melodrama, it’s clear that Margaret Thatcher was a great prime minister, if by greatness is meant ‘historical importance’. She certainly led one of the three most radical governments of the century (the equal being Attlee’s, with Campbell-Bannerman/Asquith somewhat behind). And unlike Attlee or Asquith, she was the indisputable leader of that government. You probably have to go back to the dance between Gladstone and Disraeli to find a politician who has so personally dominated British society, and they at least bounced off each other; Thatcher dominated all on her own. Britain in 1990 was almost unrecognisable from the Britain in 1979. And – what is an even greater achievement – the Britain of 2013 still looks remarkably like the Britain of 1990.

So a great prime minister, certainly. But a good one?

The inheritance

Britpop and ‘Cool Britannia’ was a reaction to the gloom of the Eighties; the Sixties counterculture was a reaction to the stuffy conformism of the Fifties; the Twenties jazz age was a reaction to the horrors of the First World War. Every decade can be read as a reaction to the decade preceding it. Except for the Noughties. The Noughties were a reaction to Simon Cowell, and were consequently crap.

This has never been truer than in the case of the 1980s. The Thatcher “revolution” (or counter-revolution, depending on your taste) was more self-consciously a reaction to the drama of the years preceding it than any other post-war government. The power of this narrative infects even the greatest of minds: when the Loose Women discovered that Thatcher had died, Carol McGiffin proffered that she supported Thatcher because she “remembered what it was like in 1979, with the winter of discontent and the three day week.” Never mind that the three day week was actually introduced in 1973 by the Conservative government of Edward Heath, of which Thatcher was a Cabinet member; it’s just too good a story to tell.

I have discussed in detail elsewhere the historical forces which caused all the trouble in the 1970s; see my earlier blogpost, ‘The Spirit of ’45 and the Spectre of ’79’. Here it will suffice for all you One Direction fans to just highlight the key events.

Edward Heath, Mrs Thatcher’s predecessor as Tory leader who appointed her to the Cabinet as Education Secretary, was Prime Minister from 1970-1974. He was elected to replace Labour’s Harold Wilson. By historical standards, the economy he inherited wasn’t too bad, although inflation was trending upwards. Heath was elected on a commitment to ‘disengage’ the government from the economy (in contrast to Wilson, who liked fiddling. With the economy, that is). Heath’s policy was all over the place: he tried to control pay (and thereby inflation), but he also abolished lending constraints on banks (which allowed the money supply to increase significantly – 72% between November 1971 and December 1973). He also u-turned on ‘disengagement’, bailing out Rolls-Royce, among others. Then in 1973, war broke out between the Arabs and the Israelis and oil prices quadrupled, with inflation shooting through the roof. But the final humiliation came when relations with the miners broke down in 1973, leading to a deliberate slowing down of work on their part. As coal stocks dwindled, Heath introduced the ‘Three Day Week’, in order to conserve energy stocks. This policy took force in late 1973, and a few months later Heath called a general election on the slogan “Who Governs?” Needless to say, he lost.

Labour returned under Harold Wilson to find the worst economic problems since the war. Inflation peaked at 24.2% in 1975; the following year, in 1976, the British Government had to turn to the IMF to receive a bailout. (The mythology and misunderstanding surrounding this episode is so great that I shall assess it in a separate post in the future). British economic prestige – already comparatively low when set against others such as Germany or France or Japan – sunk even lower and we became known as ‘the Sick Man of Europe’. James Callaghan (who took over from Wilson in 1976) tried to strengthen control over pay and inflation throughout his premiership, to varying degrees of success and failure. But in 1978, world oil prices once again shot up (this time, primarily because of the rising conflict in Iran) and the inflationary spirals were set off all over again. The Callaghan Government tried to hold firm – leading to increased conflict with the unions. The end result was the ‘Winter of Discontent’, which famously saw the dead go unburied and the rubbish go uncollected as gravediggers and garbage collectors (and others, including ambulance drivers) went on strike. Although the bulk of the chaos had passed by the end of the winter, the damage was done, and in May 1979, Margaret Hilda Thatcher became the first female Prime Minister in British history.

The Lady’s not for turning?

Thatcher entered office with two main targets, and one broad mission. The targets (which were related) were to bring down inflation and rein in the trade unions. The mission was to restore the British economy to competitiveness and prosperity. In her view, bringing down inflation and wrestling power away from the unions were the first steps to any such prosperity. And so Thatcher set off with a uniquely clear vision and a determination to not buckle in the way the previous Conservative government had done under Heath.

Thatcher’s inner circle were strong believers in monetarism, defined by future-Chancellor Nigel Lawson in 1980 as consisting of

two basic propositions. The first is that changes in the quantity of money determines, at the end of the day, changes in the general price level; the second is that government is able to determine the quantity of money.

This is where it gets a bit technical. But it is important to understand what the Thatcher Government went on to do, because the myth that “the lady’s not for turning” is largely erected by people who don’t understand it (see: Andrew Marr), or by people who don’t want you to understand it (see: Mrs Thatcher herself).

One of the main ways central banks tried to control demand in the economy – and thereby, control inflation – was through the setting of interest rates. When inflation picked up, this was read as too much demand, and interest rates would rise to choke off expansion. Thatcher’s monetarist advisers told her that this was unnecessary, and that the best way of controlling inflation was by attacking it at (what they took to be) its root: the money supply.

Economists use various different measurements of ‘money’ to work out how much is circulating in the economy at any given time. In the UK, the narrowest definition of money is known as M0 and consists of cash (paper money and coins) and reserves held by private banks at the central bank (the Bank of England). The broadest definition is known as M4 (though was then actually known as M3) and consists of all of the above, plus deposits in the wider economy, which are the product primarily of loans. In other words, narrow money (aka. the monetary base) is cash plus bank reserves; broad money (aka. the money supply) is cash, reserves and credit. In the UK in 2010, measurements of M0 stood at £47 billion; measurements of M4 stood at £2.2 trillion. In other words, base money made up only 2.1% of the UK money supply. The rest was credit, created through the private banking system.

So the Thatcherites believed they could control the money supply through government action. Some argued for doing so through cutting government spending; others for doing so by controlling base money. (To those who have been following recent events, this latter idea may sound suspiciously similar to the policy known as quantitative easing: you are quite right. It is the same theological balls). Ultimately the government resolved to cut the government deficit, and stopped using interest rates as a tool, leaving them instead to fall where they may.

The result was disaster.

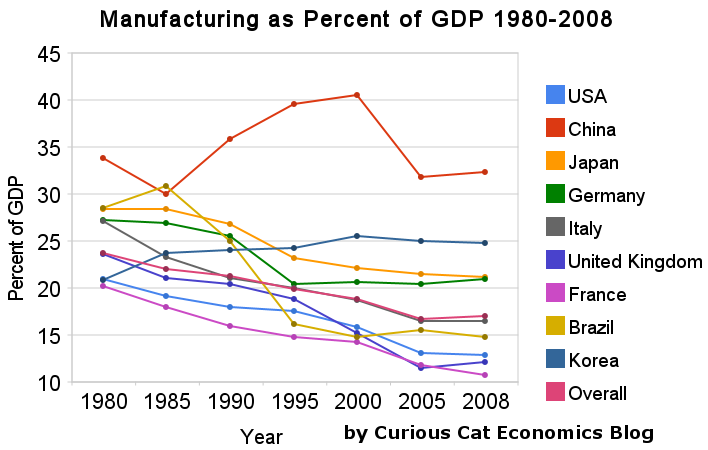

Interest rates rose sharply to reach a peak of 17%. (As you can see, they fell significantly in 1982, which played some part in the return to growth of that year, just conveniently in time for a general election! More on this later). This meant that it became increasingly difficult for businesses in Britain to invest. It also had the effect of increasing the value of the pound, which had already risen because of the tapping of North Sea oil. Consequently, British industry became exceedingly uncompetitive. Britain entered a two year recession, losing 2.0% of GDP in 1980 and 1.2% in 1981. The most catastrophic loss was in manufacturing. Output there fell by 0.1% in 1979, and then collapsed by 8.0% in 1980 and 6.0% in 1981. In 1982 it only gained 0.2% on these losses. Manufacturing in Britain was decimated, not by its inherent uncompetitiveness (though uncompetitive much of it was), not by the behaviour of the trade unions (though badly behaved they often were), but as a direct consequence of government policy. British industry needed to change, there is no doubt of that. But the sheer scale of the damage done in the first years of the Thatcher government was totally disproportionate.

Thatcher apologists would say that this was a necessary price to control inflation. Unfortunately for them, it did no such thing. Because while the monetarists predicted that directly targeting the money supply would control it, in fact it continued to grow, and what is more, its relationship with inflation is not in evidence in these years:

Increase in money supply per year / Rate of inflation

1979 14.1 13.4

1980 17.2 18.0

1981 20.9 11.9

1982 12.0 8.6

1983 13.2 4.5

(Source: Smith, D., 1992. ‘From Boom To Bust: Trial and Error in British Economic Policy’)

We can see that even as the money supply increased (despite Thatcher’s attempts to stop it) it beared very little relationship to the rate of inflation, particularly from 1981 onwards. It seems that inflation fell not because of monetary policy, but in spite of monetary policy. And what happened around this time that could be an alternative explanation for the fall in inflation?

Ho ho! What a coincidence.

The sharper amongst you will recognise that the money supply was increasing (despite the government’s efforts). But if businesses were finding it increasingly difficult to borrow, where was all this new money going?

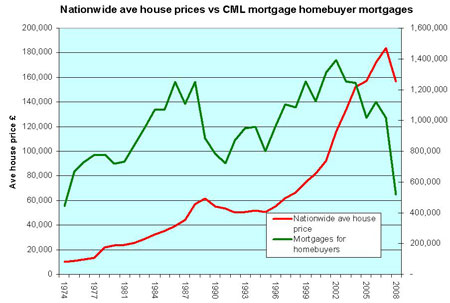

And there we have it. Net mortgage lending doubled between 1980 and 1982. By the time Thatcher left power, house prices had risen 175%. And the cost of a house relative to income had increased by a third. (The bursting of the Lawson bubble and the recession under Major did their bit to make things more affordable again, before Blair and Brown picked up the same trajectory with gusto). So here, in embyro, is the economic model that came to dominate Britain for the next thirty years: away from industrial production and towards property speculation. And while it is a phenomenon that has occurred throughout the developed world, the loss has been steeper in Britain than in almost any other country. As Germany and Japan show, economic modernisation need not mean deindustrialisation, with all the employment effects (particularly on unskilled men) that that entails.

And what of employment? We know that the Thatcher government needlessly crippled manufacturing, invented a new economic model based on speculation and asset inflation, and failed even to do the one thing it wanted to do, namely control the money supply. What was the effect of all this incompetence on employment?

Unemployment (already rising to a post-war record under the austerity measures demanded by the IMF in 1976) reached an incredible 12% – over three million people. This is particularly offensive given the Conservatives had won the 1979 election in part on the slogan “Labour isn’t working”, criticising the Callaghan Government for the rise in unemployment.

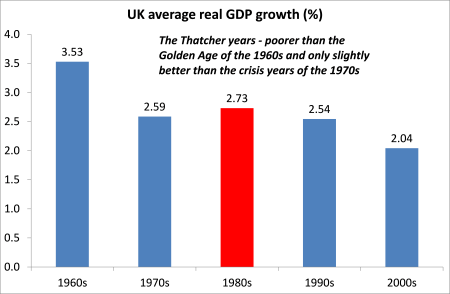

Now just look at that chart closely again and let it sink in. Two things in particular stand out. First: unemployment under Thatcher never fell to the levels it was pre-Thatcher. Throughout her term in office, unemployment was higher than she found it. Second, even more shockingly, unemployment since Thatcher has never fallen to its level pre-neoliberalism (if we take the imposition of neoliberalism as starting in 1976). In other words, Thatcher cemented an economic model which has been chronically incapable of meeting the levels of employment that existed before it. Not only that, but it hasn’t even been able to produce the same level of growth as the high-point of the apparently awful post-war consensus, the 1960s (and nor have the decades following it).

The claim therefore that all Thatcher did was remove artifical government support for employment is untrue: in fact, she swept away a policy – a commitment to full employment – which filled a need that the market has since failed to satisfy. (See my earlier post ‘The silent British jobs crisis’ for more information).

And there is good reason to believe that, far from being a terrible side effect of the government’s policy, it was consciously understood as a price worth paying. Here is the appropriately-named Lord Cockfield, Treasury Minister from 1979 to 1982, writing to the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the money supply:

Control of the money operates through the simple but brutal means of butchering company profits. Ultimately insolvency and unemployment teach employers and workers alike that they need to behave reasonably and sensibly.

Well, well.

What Maggie did next

So in 1980, amongst all this chaos – high interest rates, manufacturing collapse, rocketing unemployment – Thatcher addressed the Tory congregation and declared “You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning.” The mythologising of this moment has reached epic proportions; it is one of her most famous quotes, and there is a similar reference in the Meryl Steep film ‘The Iron Lady’. While having her dress fixed, Meryl Thatcher is accosted by her cowardly ministers who beg her to change course for fear that they might lose the next election. Thatcher is furious. “Yes the medicine is harsh, but the patient requires it.” There are only two problems with this. First, the ministers who criticised her were making quite rational economic assessments, not acting out of vain self-interest. Second, it wasn’t medicine, it was poison.

Now if you don’t follow or understand the intricacies of monetary policy (ie. you are Meryl Streep or Andrew Marr), you would be forgiven for thinking this is an accurate representation of what happened. The story is something like: Britain was a mess in the 1970s; Thatcher came along and did a lot of harsh stuff; lots of weak people and vested interests complained; Thatcher stuck to her guns; the problems of the 1970s disappeared; Thatcher saved us, give her a state funeral.

The problem here is Thatcher did not stick to her guns. The government abandoned the original monetarist policy of directly targeting monetary aggregates and reversed the rise in interest rates. All the economic indicators improved and, coupled with victory in the Falklands, Thatcher won the 1983 election. As Hywel Williams says,

This was one of the biggest economic policy U-turns post-1945. It doesn’t get the attention it deserves because it suits both Thatcher-worshippers and Thatcher-loathers to present her as steadfast or inflexible (according to taste). It also suits Lady Thatcher herself to ignore the evidence of her own pragmatism in the face of the facts. But the lady really was for turning – when Alan Walters told her she had to.

The legacy

Thatcher went on to oversee many other changes in her next two terms of office, in particular, the liberalisation of the banking system and the consequent decline in building societies and rise in property speculation. The victory over the miners following their year-long strike also had the effect of crippling trade union optimism: if the miners – the ‘aristocracy’ of the labour movement – could not stop Thatcherism, who could? The path was set for the decline of traditional manufacturing and the rise of the service industries. This legacy continues, particularly in the failure of the Coalition’s hope for an ‘export-led recovery’.

Much of the growth from 1985 onwards in fact was an enormous bubble in property and finance (sound familiar?) which promptly burst in 1988. So in a sense, the economics of the Thatcher era which conservatives so droolingly vaunt today amounted to an unsustainable boom buttressed by the two deepest recessions since the war. Yet another feather in the cap of Tory economic management.

But it was in the first term that the greatest – and most needless – damage was done. The unions had become too powerful and industry had become sclerotic. Clearly something needed to change. But the price paid in unemployment and the severity of manufacturing collapse was completely unnecessary. It was this which created the culture of hopelessness which pervaded so many parts of the country, and in many places still does. The basic claims in defence of this suffering – that it was necessary, and that Thatcher held her nerve – do not stand to scrutiny. Charles Moore, Thatcher’s official biographer, pointed out on Question Time a few nights ago that 29 million working days were lost to strikes in 1979, and that this was reduced to 2 million by the end of her premiership. Fine. But how many working days were lost to unemployment throughout her leadership? How many in 1982, when unemployment broke three million? 3 million unemployed multiplied by 240 working days lost works out at nearly 750 million working days lost due to unemployment in 1982 alone. The difference is the unemployed do not strike or disrupt production, or in fact do anything at all. They just sit there and rot and lay forgotten, faceless statistics on a government database. But the suffering and lost lives are real enough.

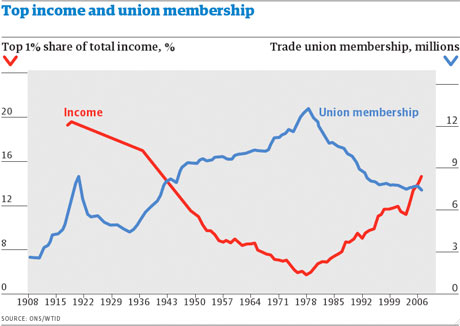

The reason feelings are so strong on Thatcher is because people only look at one side of the balance sheet. Supporters ignore or explain away the suffering; opponents do not account for the problems that preceded her. The truth is Thatcher solved the problems she set out to solve, but she did so by replacing them with a whole new set of problems. High inflation was replaced with high unemployment. Almighty unions were replaced with almighty banks. Productivity improved but the balance of payments actually worsened. Inefficient manufacturing was replaced with unstable financial services. Working days lost because of striking by labour have been replaced by many more lost because of striking by capital. It’s a mixed legacy at best. But in this week of her death, an attempt has been made to turn her into an unambiguously positive figure. This is myth-making. And as Jonathan Freedland rightly points out, this is an argument about Britain’s present and future as much as about its past. If cold but crucial leadership is what Britain required then, maybe it’s what Britain requires now? Maybe Cameron isn’t so bad afterall? This is why the government are so keen to give Thatcher a glorious send off. Such is the use and abuse of history.

If you want to know the real legacy of Margaret Thatcher, and not the myths, three charts will do.

Tory Party headquarters are welcome to redistribute this post.

Further viewing…

Thanks Ash another good read.

Thanks alot 🙂

Fantastic blog! Do you have any suggestions for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you advise starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option?

There are so many options out there that I’m completely overwhelmed .. Any suggestions? Thanks a lot!

Thanks so much for your kind comment 🙂 This is only my fourth post so I’m far from expert on this matter, but I find WordPress very easy to use. There is actually an option to buy your own domain name through them, so if your blog takes off you can then do that. So I’d recommend starting free and seeing how the traffic goes.

Thanks again for your feedback 😀

*swoons*

Thanks very much for your comment, greatly appreciated!!!!!!!!!!!

As one who lived through the years you have described I find this makes real sense. It is an excellent post which puts the death of just another post-war politician in perspective. Thank you.

Thanks NMac, I’m glad it fits with your experience!

Pingback: Sonn-tagslinks — KALIBAN (You are likely to be eaten by a grue)

Put simply, that was an excellent read. I wrote something similar a while back, not as in depth, but I discuss a lot of the same themes.

http://theconscienceblog.com/2012/11/18/privatisation-is-justified-only-if-it-results-in-competition/

Great post Iyobosa. It’s interesting how dissatisfied with utilities privatisation so many people are, and yet how it goes completely unaddressed by any of the main parties. This is a consequence of the mythic hold that Thatcherism has over British society even now: private good, public bad, etc.

Could not agree more

Thanks very much for this. Although I was alive during her reign I was quite young and never really caught up properly on why she was a monster (I just felt that she was). It’s great to supplement feelings with facts.

Good writing. I like your balance. Was Ian Hampshire Monk one of your mentors?

Thanks. ‘Mentor’ might be a bit strong, but I was certainly taught by him! Why do you ask?

Fantastic post!

It has been argued recently that the industries she decimated were going to decline anyway – and possibly this is in places true. However. left to its own devices, the decline would have been slower, with time for alternatives or modernisation to take place, much reducing the mass unemployment and the effective destruction of many commnunities where heavy industry was the main – or only – employment.

Further, the argument of high employment in Consett has recently been used as an example of effective increase in employment under the current governmment. However, most people are no longer actually employed in Consett. They were given preferential treatment in applying for alternative employment elsewhere due to an interevention programme, so they got jobs where jobseekers in those places might otherwise have done so. Hence it is a redistribution of unemployment, not a reduction.

Very interesting point about Consett!

Thank you for this; it is an incisive demolition of the myths around Thatcher. I note also your fair criticism that her opponents were often been less than clear what the problems actually were – and still are. That I hope will be the starting -point for another discussion on how we can see an

alternative to the second-generation Thatcherism of the current Coalition.

My feeling is that the problem has always been that the opposition allowed themselves to be drawn onto neo-liberal terrain, where “economy” is equated to “society” (making the latter term redundant) and thus human interactions are rational in a way that can be calculated. So we end up with very narrow discussions. Mt string-point would be that human beings by contrast are complex beings who

relate to one another in all sorts of ways, the context for such relationships being “Society”. So “economy” is but one part of “society” and is inseparable from this deeper view of human beings. This takes us into all sorts of tricky stuff like evaluating “well-being” but if we don’t do it we get hooked on reductionist narratives like Thatcherism.

Thanks for your comment Bob. You only have to look at the way the Coalition (Cameron and George “Crying” Osborne in particular) have used her death recently to try and elevate her above politics. Cameron’s use of the phrase “there is no alternative” only a few months ago is just one of the echoes of that era (and the myths surrounding it). I certainly do intend to think about alternatives in future posts, and my ideas on this chime exactly on your comments about relationships vs. economy. So keep reading! 😀

good article and lay the myth that the last week has set.

Excellent article. Just a little bit more on her destruction of the education and the ‘milk snatcher’ aspects would be great too. I lived through all of this as a teenager and subsequently and your blog is very accurate . She also made me redundant by Act of Parliament in 1989 and I heard about it on the 6 O’clock news!!!! If I were there I would turn my back for sure- this lady IS for turning.

Jane

Excellent article, probably the best assessment of the Thatcher years I’ve read this week (which, trust me, is a huge compliment!). Great use of data too, it’s effective and clear without being offputtingly polemical. Would be really interested in seeing a similar post going into more detail on the Wilson/Callaghan/Healey years. There’s a lot of rewriting of history by the right, especially around the IMF loan (I swear to God, if i hear the phrase “cap in hand” one more time…) and, while by no means a great PM, I think Jim Callaghan did the best he could in extraordinarily difficult circumstances. As has been pointed out here and elsewhere, the economy was actually beginning to recover in ’79, before Howe’s disastrous monetarist experiment plunged it back into recession.

Thanks Rob, I certainly will be writing about the 1970s in the future, especially the IMF. You’re spot on about “cap in hand” – the constant use of that phrase is a telling clue of the groupthink and received wisdom that informs talk of that period!

I just want to tell you that I am very new to blogging and site-building and honestly loved this blog. Very likely I’m want to bookmark your blog . You actually come with tremendous posts. Cheers for sharing your website page.

Fantastic article, and a rare voice of calm reflection over the last week Immediately and gratefully shared on my Facebook page.

One quibble though – 335 working days in a year? I’m assuming it’s a typo – in fact I missed it myself, but a couple of my friends have seized on it as undermining everything else you’ve said. (I’d have preferred to point it out in a private message but I don’t appear to have that option).

Thanks 🙂

Oh dear, that’s a very stupid mistake on my part! I generously gave workers four weeks holiday but forgot to factor in weekends! I’ve corrected the figure accordingly (and also changed the date to 1982, when unemployment hit three million). I don’t see how your friends think this undermines everything else though?! The argument being: Thatcher a) caused needless harm in the first term which she b) quietly u-turned on, contrary to the ‘Iron Lady’ myth. The fact that 720 million rather than 1 billion working days were lost in a year due to unemployment seems to not undermine that analysis one jot!

I completely agree – in fact I said as much to the friends in question.

This post is excellent. You set out with great clarity a section of UK history that seems to have been airbrushed out of existence by the mainstream media. I’m particularly looking forward to your post on the IMF bailout of the UK. The way you combine the historical analysis with your modern understanding of money/debt (Post Keynsian/Steve Keen I assume) gives in my view a much more accurate understanding of what happened. And I find that most refreshing. I have bookmarked your site for future reading. Keep up the blogging.

Thanks very much. Post Keynesian and Steve Keen (and also Modern Monetary Theory) – 100%!

Have you been following this? http://www.peri.umass.edu/236/hash/31e2ff374b6377b2ddec04deaa6388b1/publication/566/

I certainly have! Staggering stuff. I’ve read some of Pollin’s work before, he’s a great economist. And Thomas Herndon has just been added to an economics discussion group I’m a member of. To be fair, Rogoff and Reinhart’s book (‘This Time Is Different’) is a pretty excellent overview of the history of economic crises, but the 90% figure always struck me as arbitrary rubbish. Quite apart from the (now proven) nonsense of that number, there are two major problems with their thesis: they misconstrue causality (could it be that high public debt is a SYMPTOM of poor economic performance, rather than its cause?) and they do not understand the conceptual difference between a currency issuer, and a currency user. So while their work is interesting in terms of the data they have acquired (though even that looks suspect in light of this…), the theory behind it is completely bogus.

Are you suggesting that there is an alternative to what Thatcher did? And whats more – an alternative to todays economic system? This is the best system we have, and there is no alternative that can produce the desired effects of an economy.

What do you mean by “today’s economic system”? The neo-liberal model in the UK and North America? The social partnership model operating in Germany? The social-democratic Nordic model? The gangster capitalism of Putin’s Russia? The corporatism of Japan? The statist capitalism of post-communist China? Cultural parochialism was a key feature of Thatcherism.

So too was a tendency to conflate “economy” with”society” and assume that we all agree on “the desired effects of an economy” – i.e., high short-term profits for footloose private capital. That means that increasing social fragmentation and wider gaps between rich and poor – for which there is no rational, never mind moral, justification – can be conveniently ignored.

What a sweeping statement; “there is no alternative that can produce the desired effects of an economy.” If your objective is the excessive accumulation of wealth in an ever smaller number of hands, and the destruction of demand that that entails, then fair enough, you might be right. But if your objective is a more reasonable distribution of wealth, and a ‘healthy’ economy, then there are many alternatives to be tried, particularly those that seek to prevent the asset bubbles created by a minimal regulation of the private banking system, not to mention financial ‘products’ which seems to me to be a euphemism for extracting wealth from the real wealth generating economy. In reality the banking system should be a tiny proportion of the economy, which it ‘serves’. And not a parasite slowly killing its host.

Spot on Joe. It was when the bankers were allowed to pass themselves off as “wealth creators” rather than what they are – wealth managers – that the rot really set in.

Pingback: Iron Waspy Ladies: What Annette Funicello, Lilly Pulitzer, and Margaret Thatcher Tell Us about the Cold War – Tropics of Meta

Thanks Bob. My main concern though is the fact that there seems to be almost two realities. The propaganda propelled neo-liberal model world (and all that entails) led by the main stream media, which seems to only be of benefit to the excessively wealthy, who seems to have managed to infiltrate main stream political parties of all colours. And the real world that is plunging ever deeper into an economic, social and environmental crisis, that only a small proportion of us (including those aware of this blog) seem to know even exists. I find it quite depressing sometimes. Any attempt to raise such issues on main stream sites gets shouts of “conspiracy theorist”!

averagejoe and Bob Waugh – great comments. The ‘there is no alternative’ myth rears its ugly head once again…

If there was an alternative we would have found it by now – and the alternative in the 20th Century, the USSR, was a brutal socialist dictatorship. Socialism can’t work, it’s against human nature and that’s why it was doomed to failure.

Jesus there is so much wrong with this, where to even begin…

Firstly, the USSR was not the only alternative to Thatcherism in the 20th century. Social democracy after the war was much more successful than Thatcherism for a long time.

Second, the USSR was not socialist. What is your definition of socialism?

I’m sure the rulers of the roman, mayan, and egyptian empires thought the same thing.

You ought to ask yourself what your working definition of “human nature” is.

Selfishness and greed?

My take on ‘human nature’.

Pingback: Radically Melbournated | Tad Williams

“When the Roman emperors died, the greatest amongst them were granted an apotheosis – elevation to a divine level.

I wonder which of our months it would be most appropriate to rename ‘Thatcher’? I would suggest February, as it often feels bitterly cold.

Thank you very much for this post; I’ve always felt that Thatcherism is wrong, but am always hampered by a lack of analysis that isn’t biased by those who believe that the sun shone from somewhere it shouldn’t. Not a subject one can usefully discuss down t’ pub because nobugger knows what they’re talking about there (including me!). I am quite fond of referring to the 100p beer tokens in my pocket as ‘Thatchers’ (because they’re brassy, and pretend to be a sovereign).

I gratefully take away the following:

… and offer in payment a couple of typo alerts:

“… bring down inflation and

reignrein in the trade unions…”“… it is a phenomenon that has

occuredoccurred throughout…”Hahaha, thank you, and thank you for pointing out the typos!

Ash, video of you somewhere in here, shot by me:

Drop me an email to visionaforethought AT gmail DOT com.

(We briefly met at Lady’s T’s funeral, I was shooting video most of the time of the debates and crowd.)

Regards,

Alex

A very nice read lady/sir. I congragulate you on your efforts, please keep it going.

Cheers 🙂

Dear author,

Thanks for this. I think this is highly illuminating – and will be more so if I understand the following:

1. Why, when the Thatcher Govt resolved to control M0 by reducing the deficit (if this is true), did interest rates spike?

2. How are M0 and deficits related?

3. If they had applied controls to M3 instead of M0 at the time, what would have happened?

4. How were they able to get interest rates to drop before the 1983 election?